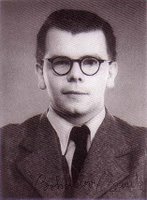

Bohuslav Brouk

While Nezval’s diaries remain a significant part of my reading matter these days, I can really only deal with his handwriting for a few hours per day. After wrestling with enough Nezval interpretation, I really have to turn to printed sources for awhile, of which the current one is another early Prague surrealist, Bohuslav Brouk.

Originally, I don’t think I had any very big plans to read much Brouk, but after I let on to my advisor that there was a psychoanalyst among the Prague surrealists, she was not about to let me ignore him. She has hopes that through reading Brouk, I will discover significant differences between the Czech and the French approaches to Freud (Freud was of great importance to the Paris surrealists, but like everyone else they liked some of his ideas and not others). Well—I wouldn’t like to say that there might not be interesting differences to be found, or, more to the point, that I wasn’t up to the challenge of reading and analyzing hundreds or even thousands of pages of psychoanalytic theory in Czech (pardon me while I quietly slit my wrists in despair)—

Um, yes, Brouk was rather prolific, although I don’t think that his late opus Plants Consumed by Man (available used in English!) needs to be on my reading list. I took a look at the titles that might be useful and proceeded to order that classic text Autosexualismus a psycherotismus (1935, reprinted 1992). It arrived with a nice surrealist cover by Karel Teige (hidden by the library binding, of course).

It rapidly dawned on me that Brouk must have been something of an infant prodigy, or perhaps just an enfant terrible. Autosexualismus a psycherotismus was published when he was only 23, at which time he had already been a founding member of the Prague surrealist group for over a year. It appears to be a compilation of everything available on his topic from Biblical days and the time of the ancient Greeks up to and including Freud, Ellis, Malinowski, Hirschfeld, and the rest of the gang. A startling number of eighteenth-century French experts are mentioned. The activities of the Japanese, the Trobrianders, sailors, prisoners, and Russian women are not left out. It is filled with scientific-looking words that I cannot find in dictionaries, although as a rule they are not that essential to one’s understanding of the gist (but anyone who knows what “lambitus” and “alosexualismus” are should be sure to enlighten me, as while I have difficulty remembering the Czech terms for turkey and pumpkin, no doubt I can change the subject of conversation away from Thanksgiving and start expounding on lambitus instead).

I should note that it isn’t necessary to my dissertation for me to absorb everything that Brouk has to say, especially when he is merely enlightening a 1935 Czech audience about what has already been said in German, French, and English. The purpose of looking at the thing is to get a sense of what he actually thought. This means that it is possible to skim the text, but not very quickly. It is not, as far as I can tell, of any importance to my dissertation what he has to say about the Japanese or the Trobrianders. On the other hand, it is hard to avoid reading more closely to see what sort of behavior has been attributed to eighteenth-century czarinas or to anonymous Russian women, and I was startled to learn that blow-up dolls were produced in French factories in the 1930s whereas the home-grown Czech variety were exorbitantly expensive. (One can only hope they were made to a higher standard than the one I once helped buy to play the role of a floating corpse in the play Surface Tension, which sprang a leak and had to be taped up.)

As with Nezval’s diaries, but for quite different reasons, there is only so much Brouk I can read in a day. The book is thoroughly researched, but I have concluded he must have been working out some form of personal issue, as I cannot imagine how else he could have assimilated so many weighty sources in such a short time without collapsing.

Then again, it does occur to me that while reading all those texts might have been mind-numbing, Brouk probably had fun discussing them with the other surrealists while he wrote. During 1934, he seems to have spent plenty of time going to cafés with Štyrský and Toyen.

3 Comments:

hey, I think I just heard on the radio that a functionalist building was returned to "Brouk a Babka." it was a former dept store. Any connection?

Yep, Brouk a Babka belonged to Bohuslav Brouk's family. He was originally supposed to join the family business and attended the obchodní akademii in Karlín (see short bio at http://www.hobulet.cz/view.php?cisloclanku=2005101902). I read somewhere or other that during World War II he advised another department store (I think it was Bilá Labut') on display aesthetics. So, maybe one of these days I'll propose a conference paper on him too. (!)

Here it is, he worked as an artistic advisor for Bílá labut' during the war. That's according to the biographical note in the book.

Post a Comment

<< Home