We Speak with Guests

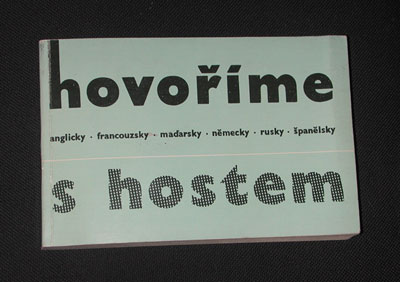

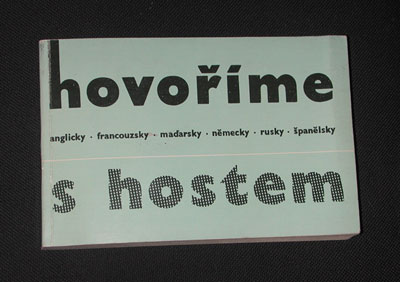

On a visit to an antikvariat some weeks back, Jesse and I encountered a remarkable item that begged to be read aloud from and which I decided needed to be purchased. (I also bought an elderly postcard that shows the source of the Vltava as being a sort of drain spout appearing, in surrealist fashion, in the middle of a forest.)

Hovoříme s hostem is a small but thick book that gives English, French, Hungarian, German, Russian, and Spanish translations of various handy phrases. For example, with its aid I can tell my guests the likes of:

“Will you please have a look at our wine-list” or “Help yourself to the cutlery at the end of the serving line.”

I can also announce, “Excuse me, smoking is prohibited in here” and “No meat is served today.” After all, it’s important to let my guests know where I draw the line.

If guests want to borrow my phone, I can sternly say “You’ll get telephone tokens in the cloakroom.”

If I wish to draw their attention to the periodicals in the basket (see earlier post about Cosmopolitan) I can inquire “What magazines or newspapers can I bring you?” After all, I am sure that someone will want to read my old copies of Ateliér, and of course everyone who visits wants to see what Cosmo recommends to “Turn Him On Like Crazy.”

If I am feeling a little rushed and overwhelmed at the outset, I can say “Excuse me I’ll first set the table a bit.”

In certain circumstances, I might be obliged to tell a guest “A gentleman [lady] was asking for you. He [She] will call again at six.” This will be especially useful if I’m unsure of the gender of the caller, for instance if s/he provides evidence of hermaphroditism. (It’s always possible that one of my soirees might begin to resemble something out of Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood, although this has not happened thus far.)

If guests begin to seem restless, I can say “I recommend you to stay for a while, there’ll be some music.” Or, if their fidgeting appears to relate to an addiction of some kind, I can state “Here are the cigarettes and matches.” After all, there is a pack of ancient cigarettes out on the balcony that may as well get used up.

If the guests are very energetic, I can assure them that “There’ll be dance music from nine till two a.m.” After that point, when I may be starting to feel a trifle weary, I can inquire “Up to what time does dancing go on?” and, if they show no signs of ceasing their exertions, I can let them know that “You can switch to the club where they close as late as four a.m.”

Musically speaking, Jesse and I were interested to note that the translations in Hovoříme s hostem are not always entirely accurate. “Dnes večer vystupuje cimbálový soubor” is rendered into English as “Tonight there’s a performance of a cymbal group.” We are a little nervous at the thought of a group of crazed percussionists taking the place of the cimbalom band. I don’t think that “un ensemble de cymbaliers” is probably correct either, although I expect the Hungarians will be safe with their “cimbalmos-együttes.” (At least, I know that the együttes part can’t be too far wrong, as it is one of the only words I know in Hungarian.)

Once the guests have dealt with the cymbal or cimbalom group (presumably it would be in my living room), I can tell them “That’s the well-known singer K.” I’d like to know whether the English translation uses the form “K” as a tribute to Kafka, as the Czech, Hungarian, German, Russian, and Spanish refer to “Krosnová” (not a singer I have heard of). The French apparently require greater detail, as they are told she is “Irène.” Why she will be crashing my party is another matter entirely.

As things wind down, I can say “We serve six special kinds of coffee” and “I can recommend you this fruit gateau.” Being an obliging hostess, I can add “Of course you can have whipped cream,” as I have the use of a high-tech mixer that has already aroused great interest among my guests. Furthermore (perhaps a little late in the game), I can state “Sorry, drivers mustn’t be served alcoholic drinks.”

Being an obliging hostess, I can add “Of course you can have whipped cream,” as I have the use of a high-tech mixer that has already aroused great interest among my guests. Furthermore (perhaps a little late in the game), I can state “Sorry, drivers mustn’t be served alcoholic drinks.”

If it seems to me that financial remuneration would be desirable for my services, I will be able to tell guests “I’ll have your bill made out.” If I wish to be picky (or they are waving 1000Kč notes at me), I can ask “Have you got small change please?” If I wish to be really, really picky, I can demand to know “How many crescents or rolls did you have?” It may, however, be necessary in some cases to state “I’m afraid we can’t exchange your money” (if they attempt to pay in Monopoly bills or Transnistrian currency).

Likewise, if I wish to make it clear that I am not too inebriated to have noticed that they are total strangers who wandered in off the street, I can say “I didn’t catch your name. Would you write it down for me please.” If they balk, I can say “Will you please show me your passport.” (You never know when that sort of information will come in handy, or for that matter who might be interested in purchasing the passports.) When I withhold the passport for later sale, I can say, first, “I’ll return the passport in a minute, as soon as I’ve filled in the registration form,” and then, when the gate-crashers get nervous, “You’ll get your passport again in about half an hour” or, better yet, “You’ll get your passport at the porter’s lodge tomorrow morning.”

On the other hand, if my guests are especially good company, I can announce “I can offer you a single room with extra bed” or “I can offer you one of our best rooms.” (I don’t know where the extra bed would come from, but I gather that my couch is a very desirable berth.) If I can’t remember how many people I am already housing, I can say “I’ll have a look which room is still free,” which will give me an excuse to see what everyone is up to in the other rooms. I can then say “Yes, we’ve still some free beds,” meaning that everyone else is passed out in the tub, smoking on the balcony, or is having sex on the kitchen table (see Jesse’s report on the IKEA survey regarding the latter). If I feel extremely obliging, I can say “I’ll gladly help you unpack your luggage” or even “You can ring the bell whenever you need, there’s night service here.” After all that night service, to be sure, I might be obliged to promise “Tomorrow your clothes will be in order again.”

If need be, I can say “We’ve prepared 25 rooms for your group,” although I am not certain where these rooms would be. Perhaps tents could be erected on the hill behind my building. If things get that elaborate, I might have to say “Here is a breakfast voucher worth twelve crowns.” Or, more realistically, I could admit “I’m afraid I can’t accommodate the whole party at one place.”

If I should happen to fall in love with a guest (zamilovat), I might be so bold as to state “Our employee will take you to the aliens’ department and they’ll prolong the validity of your visa.” (As I have no employees, this would be a complete fiction, but when one is in love, the truth is sometimes a little flexible, ie one offers the moon whether or not it is actually available. Or so I’m told.)

If I decide to put my guests to work, I will be able to say “My shirt needs washing and ironing,” “Could you sew on this button,” and “Can you prepare a bath for me?”

If there is some question as to whether my guests plan to move in permanently, I can delicately inquire “How long do you intend to stay?” Or I can suggest “You’ll get all information about accommodation facilities at the Čedok travel agency.” (Čedok has survived over eighty years, through capitalism, communism, and more capitalism, so they must know something by this time.) If the guests are obdurate, I could say “We’ll try to get the air-ticket for you immediately” and follow that up with “The plane takes off at 13.30.”

If my guests (or I) are beginning to hallucinate, I might find myself saying things like “Here is the fishing licence valid for a week” or “For your children, we’ve got sleds here.” I might also proclaim that “The porter will get you the deckchairs and the parasol,” “The elevated construction for washing cars is behind building number three,” or “Of course, meetings with young sportsmen can also be arranged for, either by the Czechoslovak Youth Travel Agency or the Sport-Turist.”

If I have really lost my mind I might say “I can recommend you jugged hare in cream sauce.” (This, however, is not bloody likely!)

Eventually, I might decide that “I’d like to go to a nice bungalow camp for a few days,” or I might find myself asking “How much is a seven-day trip in southern Slovakia?”

Then again, perhaps I would merely state, “I should like one first class ticket for the express to Brno.” Let Jesse have guests for a change. After all, there is more room on his kitchen floor for the orgiastic guests; my own kitchen table might actually be from IKEA (although it looks of higher quality) and might not stand up to the rigorous use of all these hypothetical guests who would be eager to show IKEA that Czechs (and other nationalities) really do go at it in the kitchen. I could sleep on the special guest mattress (I have forgotten whether it came from IKEA or Tesco), experience again the amazing scalding water from the Karma heater, and finally have a cimbalom lesson and visit the Václav Špála exhibition. If no other guests show up to take over the kitchen, a relaxing weekend could conceivably be had.

(Hovoříme s hostem was compiled by Antonín Žižkovský, Jiří Čech, and Jiří Krupička, and sold for 24 Kč in 1983. Due to capitalist inflation, I had to pay 78 Kč for the gently used, somewhat yellowing copy that is now sitting on my couch.)

Hovoříme s hostem is a small but thick book that gives English, French, Hungarian, German, Russian, and Spanish translations of various handy phrases. For example, with its aid I can tell my guests the likes of:

“Will you please have a look at our wine-list” or “Help yourself to the cutlery at the end of the serving line.”

I can also announce, “Excuse me, smoking is prohibited in here” and “No meat is served today.” After all, it’s important to let my guests know where I draw the line.

If guests want to borrow my phone, I can sternly say “You’ll get telephone tokens in the cloakroom.”

If I wish to draw their attention to the periodicals in the basket (see earlier post about Cosmopolitan) I can inquire “What magazines or newspapers can I bring you?” After all, I am sure that someone will want to read my old copies of Ateliér, and of course everyone who visits wants to see what Cosmo recommends to “Turn Him On Like Crazy.”

If I am feeling a little rushed and overwhelmed at the outset, I can say “Excuse me I’ll first set the table a bit.”

In certain circumstances, I might be obliged to tell a guest “A gentleman [lady] was asking for you. He [She] will call again at six.” This will be especially useful if I’m unsure of the gender of the caller, for instance if s/he provides evidence of hermaphroditism. (It’s always possible that one of my soirees might begin to resemble something out of Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood, although this has not happened thus far.)

If guests begin to seem restless, I can say “I recommend you to stay for a while, there’ll be some music.” Or, if their fidgeting appears to relate to an addiction of some kind, I can state “Here are the cigarettes and matches.” After all, there is a pack of ancient cigarettes out on the balcony that may as well get used up.

If the guests are very energetic, I can assure them that “There’ll be dance music from nine till two a.m.” After that point, when I may be starting to feel a trifle weary, I can inquire “Up to what time does dancing go on?” and, if they show no signs of ceasing their exertions, I can let them know that “You can switch to the club where they close as late as four a.m.”

Musically speaking, Jesse and I were interested to note that the translations in Hovoříme s hostem are not always entirely accurate. “Dnes večer vystupuje cimbálový soubor” is rendered into English as “Tonight there’s a performance of a cymbal group.” We are a little nervous at the thought of a group of crazed percussionists taking the place of the cimbalom band. I don’t think that “un ensemble de cymbaliers” is probably correct either, although I expect the Hungarians will be safe with their “cimbalmos-együttes.” (At least, I know that the együttes part can’t be too far wrong, as it is one of the only words I know in Hungarian.)

Once the guests have dealt with the cymbal or cimbalom group (presumably it would be in my living room), I can tell them “That’s the well-known singer K.” I’d like to know whether the English translation uses the form “K” as a tribute to Kafka, as the Czech, Hungarian, German, Russian, and Spanish refer to “Krosnová” (not a singer I have heard of). The French apparently require greater detail, as they are told she is “Irène.” Why she will be crashing my party is another matter entirely.

As things wind down, I can say “We serve six special kinds of coffee” and “I can recommend you this fruit gateau.”

Being an obliging hostess, I can add “Of course you can have whipped cream,” as I have the use of a high-tech mixer that has already aroused great interest among my guests. Furthermore (perhaps a little late in the game), I can state “Sorry, drivers mustn’t be served alcoholic drinks.”

Being an obliging hostess, I can add “Of course you can have whipped cream,” as I have the use of a high-tech mixer that has already aroused great interest among my guests. Furthermore (perhaps a little late in the game), I can state “Sorry, drivers mustn’t be served alcoholic drinks.”If it seems to me that financial remuneration would be desirable for my services, I will be able to tell guests “I’ll have your bill made out.” If I wish to be picky (or they are waving 1000Kč notes at me), I can ask “Have you got small change please?” If I wish to be really, really picky, I can demand to know “How many crescents or rolls did you have?” It may, however, be necessary in some cases to state “I’m afraid we can’t exchange your money” (if they attempt to pay in Monopoly bills or Transnistrian currency).

Likewise, if I wish to make it clear that I am not too inebriated to have noticed that they are total strangers who wandered in off the street, I can say “I didn’t catch your name. Would you write it down for me please.” If they balk, I can say “Will you please show me your passport.” (You never know when that sort of information will come in handy, or for that matter who might be interested in purchasing the passports.) When I withhold the passport for later sale, I can say, first, “I’ll return the passport in a minute, as soon as I’ve filled in the registration form,” and then, when the gate-crashers get nervous, “You’ll get your passport again in about half an hour” or, better yet, “You’ll get your passport at the porter’s lodge tomorrow morning.”

On the other hand, if my guests are especially good company, I can announce “I can offer you a single room with extra bed” or “I can offer you one of our best rooms.” (I don’t know where the extra bed would come from, but I gather that my couch is a very desirable berth.) If I can’t remember how many people I am already housing, I can say “I’ll have a look which room is still free,” which will give me an excuse to see what everyone is up to in the other rooms. I can then say “Yes, we’ve still some free beds,” meaning that everyone else is passed out in the tub, smoking on the balcony, or is having sex on the kitchen table (see Jesse’s report on the IKEA survey regarding the latter). If I feel extremely obliging, I can say “I’ll gladly help you unpack your luggage” or even “You can ring the bell whenever you need, there’s night service here.” After all that night service, to be sure, I might be obliged to promise “Tomorrow your clothes will be in order again.”

If need be, I can say “We’ve prepared 25 rooms for your group,” although I am not certain where these rooms would be. Perhaps tents could be erected on the hill behind my building. If things get that elaborate, I might have to say “Here is a breakfast voucher worth twelve crowns.” Or, more realistically, I could admit “I’m afraid I can’t accommodate the whole party at one place.”

If I should happen to fall in love with a guest (zamilovat), I might be so bold as to state “Our employee will take you to the aliens’ department and they’ll prolong the validity of your visa.” (As I have no employees, this would be a complete fiction, but when one is in love, the truth is sometimes a little flexible, ie one offers the moon whether or not it is actually available. Or so I’m told.)

If I decide to put my guests to work, I will be able to say “My shirt needs washing and ironing,” “Could you sew on this button,” and “Can you prepare a bath for me?”

If there is some question as to whether my guests plan to move in permanently, I can delicately inquire “How long do you intend to stay?” Or I can suggest “You’ll get all information about accommodation facilities at the Čedok travel agency.” (Čedok has survived over eighty years, through capitalism, communism, and more capitalism, so they must know something by this time.) If the guests are obdurate, I could say “We’ll try to get the air-ticket for you immediately” and follow that up with “The plane takes off at 13.30.”

If my guests (or I) are beginning to hallucinate, I might find myself saying things like “Here is the fishing licence valid for a week” or “For your children, we’ve got sleds here.” I might also proclaim that “The porter will get you the deckchairs and the parasol,” “The elevated construction for washing cars is behind building number three,” or “Of course, meetings with young sportsmen can also be arranged for, either by the Czechoslovak Youth Travel Agency or the Sport-Turist.”

If I have really lost my mind I might say “I can recommend you jugged hare in cream sauce.” (This, however, is not bloody likely!)

Eventually, I might decide that “I’d like to go to a nice bungalow camp for a few days,” or I might find myself asking “How much is a seven-day trip in southern Slovakia?”

Then again, perhaps I would merely state, “I should like one first class ticket for the express to Brno.” Let Jesse have guests for a change. After all, there is more room on his kitchen floor for the orgiastic guests; my own kitchen table might actually be from IKEA (although it looks of higher quality) and might not stand up to the rigorous use of all these hypothetical guests who would be eager to show IKEA that Czechs (and other nationalities) really do go at it in the kitchen. I could sleep on the special guest mattress (I have forgotten whether it came from IKEA or Tesco), experience again the amazing scalding water from the Karma heater, and finally have a cimbalom lesson and visit the Václav Špála exhibition. If no other guests show up to take over the kitchen, a relaxing weekend could conceivably be had.

(Hovoříme s hostem was compiled by Antonín Žižkovský, Jiří Čech, and Jiří Krupička, and sold for 24 Kč in 1983. Due to capitalist inflation, I had to pay 78 Kč for the gently used, somewhat yellowing copy that is now sitting on my couch.)

3 Comments:

Haha. Well, thank goodness that you can only give them "one" ticket for the express to Brno. :) At least they won't show up all at once!

Regarding the aliens, don't forget that (according to the film Samotaři) something about the soil around Prague attracts UFOs. They could be referring to more than just non-Czech "aliens." :)

No, no, I will be getting the ticket for the express to Brno (although if the alien guests choose to follow, there is not much I can do about it, I suppose). As for the UFO aliens in Prague, of which I daresay there must be quite a few, I hope I will not be offering to extend any of their visas. Unless, of course, they are awfully scintillating company.

Oh, I love it! Reminds me of the Russian-Polish phrase book I purchased prior to a trip from Moscow to Warsaw some years ago. Great write-up!

Post a Comment

<< Home